This month’s newsletter and playlist is focused on my newest book, Brilliant Silence. It is a project six years in the making that I debuted this month at the 2022 Codex Foundation Fair, an international fine press and book arts fair in Richmond, CA. The playlist is comprised of music I listened to over the last two years of working on this book most intensely, along with songs that run alongside the themes of the book. However, if I’m completely honest, the real soundtrack to completing this book is the Dead Eyes Podcast, which is one of the most charming, touching, and inspiring audio experiences I have had in years.

The text that follows is admittedly lengthy but I wanted a place to write out some thoughts about the process of making this book, how I came to understand the concepts of this book, and finally the production and higher than usual pricing of this book. I’ve broken the writing into sections with headers in case you are more interested in specific topics.

If you’d like to familiarize yourself with this book before you dive deeper, there is a video of the book on my website. If you are just here for the music, that’s ok too. It’s heavy on indie rock of the last 5 years with vague chamber pop and electronic influences.

#8 Brilliant Silence

Listen here on Spotify. Listen here on Youtube Music, with lots of videos.

Clams Casino - Swervin

Field Report - Push Us Into Love

Claude Debussy - Suite Bergamasque

Big Theif - Cattails

The National - You Had Your Soul With You

Trentemoller - No More Kissing In The Rain

M83 - Teen Angst

Mount Kimbie - Delta

Francis and the Lights - Like a Dream

Vagabon - Full Moon In Gemini

Yumi Zouma - Cool For A Second

Bibio - Curls

Ennio Morricone - Once Upon A Time In The West

Billy Bragg & Wilco - Remember the Mountain Bed

Vetiver - All We Could Want

Fionn Regan - Cape of Diamonds

Rostam - In a River

Henry Jamison - Still Life

Wild Pink - Track Mud

Matthew Halsall - Sailing Out To Sea

Valley Maker - Beautiful Birds Flying

Broken Social Scene - Anthem For A Seventeen Year Old Girl

The Polyphonic Spree - Days Like This Keep Me Warm

Hovvdy - So Brite

The Tallest Man On Earth - My Dear

Grandchildren - Sunrise

Mew - Sometimes Life Isn’t Easy

The 1975 - I Like It When You Sleep…

Kishi Bashi - hahaha pt 1

Yazoo - Only You

The LK - Down By Law

Erik Satie - 3 Gymnopedies

Bibio - Haikuesque

Pinegrove - Endless

Dear Nora - Walking In The Hills

Frightened Rabbit - Still Want To Be Here

Madi Diaz - History Of A Feeling

Sigur Ros - Rembihnutur

On Books & Photography

I began making books as my primary artistic output around 2014. I was always uncomfortable with the weight placed on a single painting or photograph and how they shout from the wall. Books are a form in which I can compile collections of images and words until they are right. Books are also a medium in which one makes multiple copies, creating more accessible experiences and ownership. Often my publications are fast and improvisational, bound up in some sort of contextual urgency, while others are projects I’ve considered for extended periods of time before I start to make them, especially my collaborative publications. Occasionally, projects come along that have to sit and mature and reveal themselves over time. My newest book, Brilliant Silence, is one of these projects.

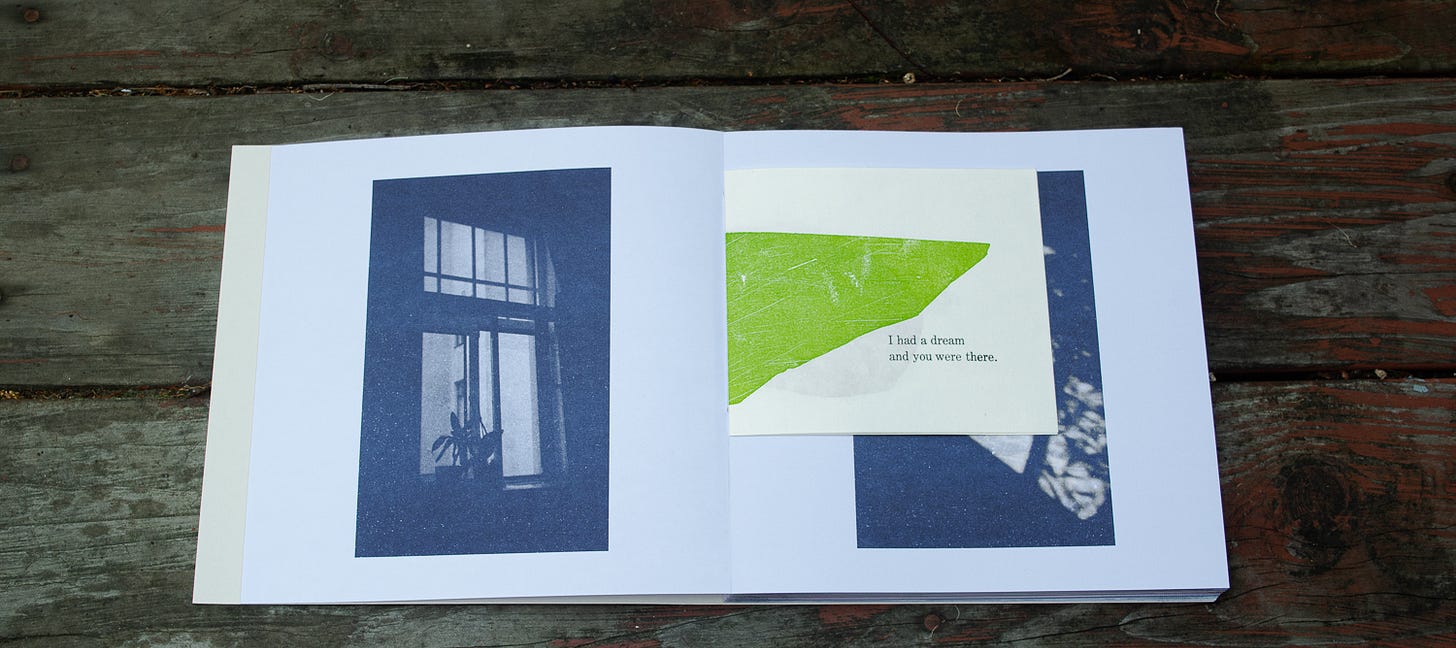

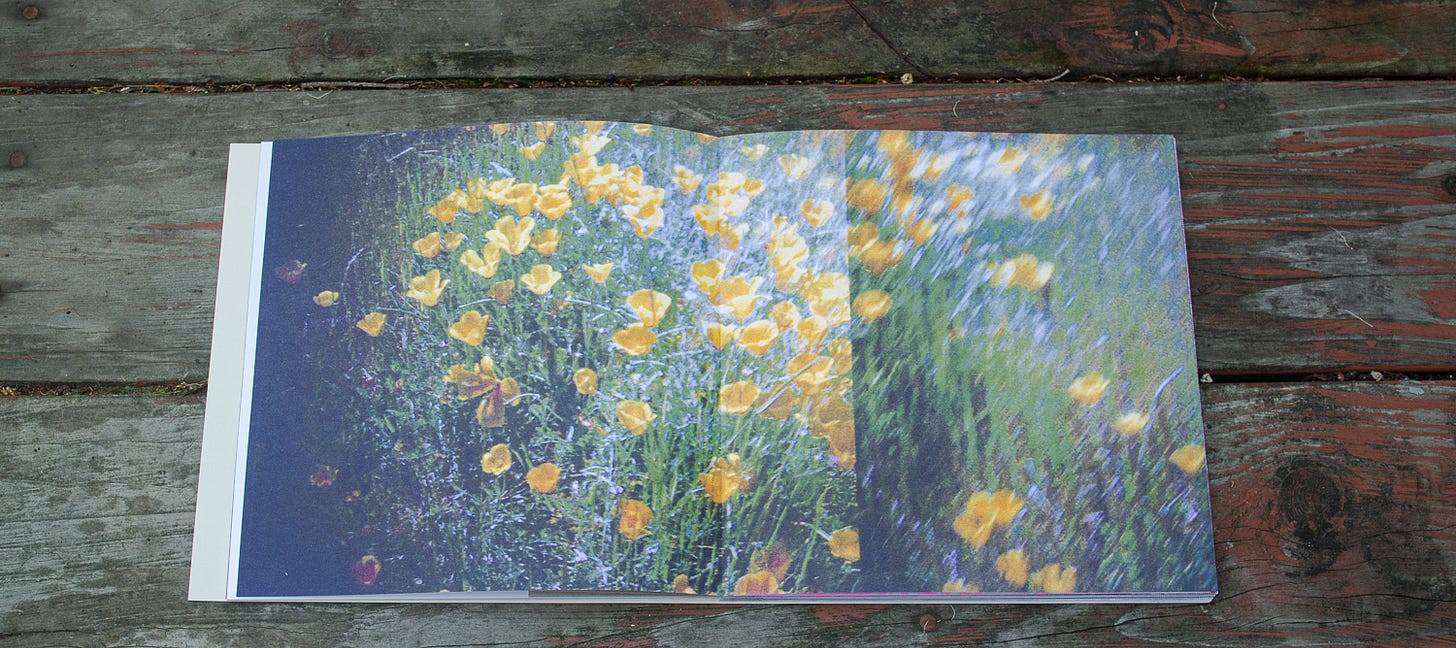

I do not consider myself a photographer — for reasons I have not completely figured out myself honestly — but the majority of my work begins as photographs. Specifically, they begin as analog film photographs taken on 35mm or 120mm film with a cheap plastic camera called a Holga. The overarching conceptual link in all of my work is an interest in memory; the fallacy, the malleability, the relativity, the way our memories often become abstract figments nestled away in our minds. Holgas are not the camera you would use if you want to take sharp high quality photos, but to me, they are the camera you want to use if you want to capture images that look like how a memory feels. They are impossible to focus, they have faulty construction, and the user has complete control over the advancement of the frames. I carry one with me at all times, especially while traveling, taking photos rather indiscriminately, building up an archive of images for eventual use.

Scandinavia

One of the first images in Brilliant Silence was taken outside of an apartment we had rented in Copenhagen’s meatpacking district in 2016. It was the spring break of my second year of grad school and my wife was living in Uganda at the time. Denmark was the cheapest flight with similar travel times we could find. A photo of a streetlight, I admit, it’s not the most interesting photo in the world at first glance, but it struck me. I wanted to figure out a way to use it as soon as possible, but all of my thesis work involved Poland and to sneak this in felt disingenuous. I taped it to my wall to continue looking at it along with a few other images from that trip. Over the next few years I continued to take photos, mostly of Western American landscapes. I’ve attempted to begin multiple projects about the American Southwest, the region the Colorado of my youth felt like it belonged to in the 80’s and 90’s before Denver became an urban hotspot in the 21st century, only to lose the thread before I even had a grasp on it.

In the summer of 2019, two significant life events occurred: 1. I purchased a Nintendo Switch and devoted nearly 60 hours to playing Breath of the Wild, and 2. I visited Finland, experiencing the midnight sun for the first time. For those unfamiliar with contemporary video games, Breath of the Wild is an installment within the Legend of Zelda franchise, widely held as the greatest video game ever made due in large part to its open world style of play in which you can endlessly explore expansive landscapes. For those unfamiliar with regions of the earth far enough north to cause the midnight sun, the sun never goes down and the human construct of time completely evaporates.

These seem unrelated, I’m aware. However, the older I get the more I suffer from intense jetlag. Our first week in Finland, I doubt I got more than 3 hours of sleep a day. I spent many of the hours in the middle of the night awake, sun peaking through the windows, wandering the plains of Hyrule. During the day, we would walk along piers and stroll through parks and I would have to constantly decipher menus in Finnish in order to feed my body the calories it needed to keep moving on such lack of rest. I moved through space with what often felt like an out of body experience where controlling my movement felt exceptionally taxing. Typically when I move through new spaces I’m focused and trying to take everything in. In this state, I was unable to look for anything in particular while still stopping to take photos of moments that caught my eye; patches of wild flowers, furniture abandoned in parks, the complete emptiness of urban centers at hours the light would suggest should be bustling. The sense of wonder I felt exploring a new country bled into that I felt exploring a make believe world to an extent the two were undeniably influencing each other as I tried to find a temporal space to hold on to.

I eventually returned home to a dozen rolls of film, with a number of frames worthy of joining that wall of orphan images that began with those photos from Denmark three years earlier. I began to make test prints with these images, trying to figure out what they might be.

2020

Spring 2020 came around and our world ground to a halt. Like so many, my career collapsed, relationships existed purely through electronic communication, my list of responsibilities and purposes shifted and shrank. I initially coped by extensively organizing and listing everything I could, a futile attempt to understand the uncertainty of the world by cataloging what I felt I could control. This included thinking it was time to make sense of my orphan wall of photographs and figure out whatever this project I’d been mulling over was.

When I ran out of things to organize, I started to head outdoors, an activity that was not exactly my first choice in the before times. We began to familiarize ourselves with our local network of trails through redwoods and watersheds and prehistoric volcanoes. I would take long drives with the intention of ending up somewhere I had not been before just to take a walk once I arrived there. I began to fly fish, largely as an excuse to find remote rivers I could stand in.

My collection of images continued to grow. I began to think the work I was making and the desire to be outdoors was related to youth, to wonder, to that same excitement around exploration. I made test prints and drove around the city to deliver them to friends as a way of trying to simulate the exchange of ideas through art and force brief human connections. That summer, I was able to attend Macy Chadwick’s In Cahoots Residency as an emergency fill in for a resident who had to postpone due to travel restrictions. I felt I had started to make enough sense of the project to work on a collection of text pages for the book. Only someone compelled with youth like wonder and naivete would think creating pages for a book you have not fully conceived of yet would be a good idea. I spent the first day in a panic. I was uncertain of what exactly I was making, I contemplated how futile it felt to make my work in the wake of the dual health emergencies and racial uprisings occurring across the country. I suppressed the anxiety as I had for months, by driving to the coast with the intention of bringing oysters back for the rest of the residents.

On this drive, I pulled over just before sunset next to the brackish waters and breathed in the damp salty air. It smelled completely like home; the coastal California I’ve resided for over 10 years. It also brought back a sensory memory of Scandinavia. This was where I first made the connection of how much our new reality of sheltering in place and avoiding others was so similar to my headspace to those first weeks in Finland, when time was nothing but a construct of which I felt my connection with unraveling.

The next morning I pushed out a collection of texts somewhat resembling poetry I frantically sent to my friends Rebecca Ackermann and Alyson Provax, who helped me attempt to make sense of it all. I tore down sheets of paper I had been saving since a residency in Puebla in 2017 with my friend Erin Martinez to be the surface for my writing. Inspired by a book my friend Annegrette Frauenlob made while essentially stranded at the residency in the first months of the pandemic and unable to return home to Germany, I decided the pages needed graphic elements and began to use the structures of the old farm buildings as collaborators in physical weathering of linoleum sheets. Over the four following days at In Cahoots, I’d print over 2000 impressions on a Vandercook Universal 3 to create text pages for a book that did not yet exist. These pages would find an extended home in an archival box under my studio couch.

Returning home meant returning to reality, or the strange version of reality we found ourselves in. There began to be talk of vaccines and an imminent “return to normal” split screen along stories heralding the death of cities due to the droves of urban dwellers abandoning their downtown apartments for rural living in Montana or the more spacious exurbs of Texas. I was not alone in my desire to disappear into nature, as the National Parks became overwhelmed with visitors and Americans rediscovered them, myself included. A road trip to Glacier National Park provided an outsized portion of images in this book, as we traveled north on small state highways to inevitably cohabitate with other humans for the first time in nearly a year. It would be at the top of the Going To The Sun Road that I would have my first panic attack in years, a jolt reminding me that while we may be seeking normalcy we would not be finding it soon.

That winter, I experienced the deepest depression of my life so far. I discussed it in my book Deciduous, a companion book of sorts to Brilliant Silence in which I began to work through what all I had been collecting over the previous years. I began to understand part of my desire to be in nature was that pursuit for normalcy and a sense of order. We had been living in constructed environments of urban planning which were void of the life it required, sharing walls with neighbors we weren’t supposed to see. Nature on the other hand, does not need schedules or productivity or industry. I had tried to construct fragments of our previous society, trying to simulate my social norms, and failed. To be in the natural world is to exist within a place exactly as it was created to be. Left to their own devices, trees will grow and rivers will flow and flowers will bloom regardless of the happenings of society. Which I guess is to say I found that to be in nature is not to escape reality, but rather it is to find it. In this I do not mean to sound pollyannaish, or like a romantic naturalist; I’m a strong believer of urban living being central to the human experience’s success now and for the future. However, I believe for the last two years, that has been a fractured construct and we are a people who need a semblance of stability. I also believe we are making progress towards regaining that former stability, or something like it, for better or worse.

In Production

It’s from this point of view I was able to finally cull down the 34 images that would be Risograph printed to represent 6 years of images and 2+ years of trying to make sense of how the work I was making related to the world around me. However, a year and a half later, I still had not figured out how exactly I would construct this book. Risograph provides a number of benefits and challenges which would need to be considered with the previously printed text pages that were originally intended for sewn signature based book binding and the multi page fold out spreads I was planning to insert throughout the book. I was unfamiliar with drum leaf binding before Montana based photographer Ian van Coller would give an artist talk to the Colophon Club about his artists books which all utilize this binding technique in which full spreads are printed, folded, and then adhered together from the spine and reverse facing pages. Ian’s talk was like the 4th of July in my head and I realized this was the method I had been looking for.

With structural plans decided, I would spend almost 2 months printing nearly 7000 impressions on our Risograph MZ 1090 in order to print enough pages to create a final edition of 40 books, with a potential 10 additional APs. They were created with the help of [color/shift] color profiles created by Travis Shaffer at the University of Missouri School of Visual Studies, as well as separations created within Spectrolite, a project by Seattle based artist initiative ANEMONE (Amelia & Adam Greenhall), two projects that exemplify the incredibly generous and collaborative nature of the Risograph community.

Once printed, the multi page fold out images must be creased and glued together and then, along with each text page, hand sewn into their companion page. Once completed, all pages are folded and arranged for spine gluing within a book press, followed by hand adhering each page’s reverse to simulate the effect of dual sided pages. Finally, each copy is trimmed to a finished size of 8x8”. In all this binding process takes several hours per copy to complete.

The Bottom Line

In recognition of the time and resources that go into the production of this book, paired with the relatively low edition size, I chose to price Brilliant Silence at $420. This price is low compared to a painting or sculpture, but admittedly far higher than the majority of projects I publish, typically ranging from $15 - 30 — prices myself, the artists I work with, and my fellow riso publishers tend to adhere to because we believe art and art books should be accessible and affordable. However, in setting that price point, we are typically printing in edition sizes of 200 - 1000 to extend earning potential. The reality is that most of us are able to price our publications this low because we own the machines and are willing to forgo compensation for our labor for anticipated earnings from the sale of books.

This is not the situation for most artists that may hire a studio to contract print books for them, and pricing their work competitively undercuts their ability to earn fair compensation for their art and labor. With this in mind, beyond the labor involved in the construction of the book, I wanted to price Brilliant Silence in a way that would reflect what someone who had hired me to print the book would need to charge to make the project feasible. This is of course to say nothing about the 40-60% cut a gallery may take from the sale of a book and the 25% they will need to pay in taxes.

It is a bit of an experiment and it sits in conflict with my desire for publications to be affordable and accessible. But this is also a project that involved years of thinking, traveling, film developing, and making. I think there is space within the medium for $15 books as well as $1500 books, and for an artist to make both.

I still have several copies to bind, so I will continue to live with this book physically, as well as mentally while I continue to wrestle with what it all means. I will say I’m happy to have it in the world and I hope you are able to see it and experience it in some form or another.

Thanks for your time, as always.